introduction

Scar is defined as ‘‘the fibrous tissue that replaces normal

tissue destroyed by injury or disease’’.(1) Causes of acne scar

formation can be broadly categorized as either the result

of increased tissue formation or, more commonly, loss or

damage of local tissue.(2)

Clinical manifestations of acne scars as well as severity of

scarring are generally related to the degree of inflammatory

reaction, to tissue damage, and to time lapsed since the onset

of tissue inflammation.(3, 4) There have been attempts to

classify acne scars in order to standardize severity assessments

and treatment modalities.(3, 4) However, consensus

concerning acne scar nomenclature and classification is still

lacking.(3)

clinical classifications

In 1987 Ellis et al. proposed an acne scar classification system

and utilized the descriptive terms ice pick, crater, undulation,

tunnel, shallow-type, and hypertrophic scars.(5) Langdon, in

1999, distinguished three types of acne scars: Type 1, shallow

scars that are small in diameter; Type 2, ice pick scars; and Type

3, distensible scars.(6) Lately, Goodman et al. proposed that

atrophic acne scars may be divided into superficial macular,

deeper dermal, perifollicular scarring, and fat atrophy based on

pathophysiologic features.(7)

One classification system frequently used in clinical practice

for acne scars is based on both clinical and histological

features.(8) Acne scars are classified into three basic types

depending on width, depth, and 3-dimensional architecture:

Icepick scar•• s: narrow (diameter < 2 mm), deep, sharply

marginated and depressed tracks that extend vertically to

the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue.

•• Boxcar scars: round to oval depressions with sharply

demarcated vertical edges. They are wider at the surface

than icepick scars and do not taper to a point at

the base. These scars may be shallow (0.1–0.5 mm) or

deep (≥ 0.5 mm) and the diameter may vary from 1.5

to 4.0 mm.

•• Rolling scars: occur from dermal tethering of otherwise

relatively normal-appearing skin and are usually

wider than 4 to 5 mm in diameter. An abnormal fibrous

anchoring of the dermis to the subcutis leads to superficial

shadowing and to a rolling or undulating appearance

of the overlying skin.

Other clinical entities included in this classification are hypertrophic

scars, keloidal scars, and sinus tracts.(8) Both hypertrophic

and keloidal scars result from an abnormal excessive tissue

repair: clinically, hypertrophic scars are raised within the limits

of primary excision, whereas keloidal scars transgress this

boundary and may show prolonged and continuous growth.

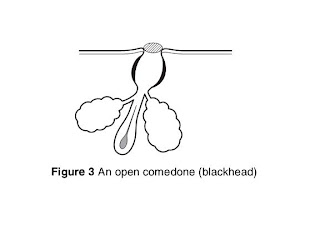

(9) Sinus tracts may appear as grouped open comedones histologically

showing a number of interconnecting keratinized

channels.(7)

Another classification is that proposed by Kadunc et al.(3)

Based on clinical appearance and relationship to surrounding

skin, acne scars are classified in this system as elevated, dystrophic,

or depressed. Other parameters include shape, consistency,

colour, and distensibility. This classification system may

also serve to assess the efficacy of various therapeutic options

based on acne scars types.(3) Kadunc’s classification is summarized

in Table 1.1.

Goodman et al. proposed a qualitative grading system that

differentiates four grades according to scar severity (Table

1.2): Grade I corresponds to macular involvement (including

erythematous, hyperpigmented, or hypopigmented scars),

whereas Grades II, III, and IV correspond to mild, moderate,

and severe atrophic and hypertrophic lesions, respectively. (10)

Interestingly, the authors consider lesion severity also according

to visibility at a social distance (> 50 cm). Moreover, since

patients may present various types of acne scars at numerous

anatomic sites (i.e., one cheek, the neck, the chest, and so

on; these single areas are defined by the authors as “cosmetic

units”), scars are further subdivided into four grades of severity

by anatomic sites involved, and the localized disease (up to

three involved areas) is classified as A (focal, 1 cosmetic unit

involvement) or B (discrete, 2–3 cosmetic units), whereas the

involvement of more cosmetic units is classified as generalized

disease, previously described in Table 1.2.

The same authors subsequently, suggested a quantitative

numeric grading system based on lesion counting (1–10,

11–20, >20), scar type (atrophic, macular, boxcar, hypertrophic,

keloidal), and severity (mild, moderate, severe). Final scoring

depends on the addition of points assigned to each respective

category and reflects disease severity, ranging from a minimum

of 0 to a maximum of 84 (Table 1.3).(11)

Finally, Dreno et al. first proposed the ECLA scale (echelle

d’evaluation clinique des lesions d’acne) (12), followed by

the ECCA grading scale (echelle d’evaluation clinique des

cicatrices d’acne) (4). According to this scoring system,

morphological aspects of lesions define the type of scars as

follows: atrophic scars (V-shaped, U-shaped and M-shaped),

superficial elastolysis, hypertrophic inflammatory scars (<2

years since onset), and keloid-hypertrophic scars (>2 years

since onset). Each scar type is associated with a quantitative

score (0, 1, 2, 3 depending on the number of lesions) multiplied

by a weighting factor that varies according to severity,

evolution, and morphological aspect. The final global score

is directly correlated with clinical severity and ranges from

0 to 540 depending on the type and number of acne scars

clinical and ultrasound correlations

Methods

Ultrasound imaging is a noninvasive technique that uses

various acoustic properties of biologic tissues. Typically, echo

signals are represented in one-dimensional diagrams (A-mode)

or two-dimensional images (B-mode).

Ultrasound of the skin is best performed by equipment

using frequencies of > 20 MHz. Using B-mode imaging,

normal skin typically shows an epidermal entrance echo, the dermal layer, and the subcutaneous layer. This technique offers

a wide range of possibilities in clinical and experimental dermatology.

It is used for the evaluation of skin tumour thickness

(e.g., basal-cell carcinoma, melanoma). Areas of research

may include scleroderma, psoriasis, and aged and photoaged

skin. Moreover, it provides an objective measurement of skin

thickness and has been utilized to assess thickness of hypertrophic

scars before and after treatment.(13)

A preliminary study was preformed in a series of

patients (N = 20) affected by various types of acne scars

in order to determine whether a correlation exists between

clinical appearance of selected scar parameters (thickness,

width, depth) with ultrasound examination. Cross-sectional

B-mode scans were obtained using a 22-MHz ultrasound

system (EasyScan Echo®, Business Enterprise, Trapani, Italy)

that allowed examination of skin sections of 12 mm in width

and 8 mm in depth.

Results

Atrophic scar•• s appear as invaginations of the skin in

which all skin layers are normally represented:

a) Icepick scars (n = 5) uniformly have a sharp, demarcated

V-shaped appearance and are characterized by a

narrow diameter at the surface (usually < 2 mm) and

a vertical extension that reaches a depth corresponding

to the deep dermis (Figure 1.1a–1.1b).

b) Boxcar scars (n = 5) uniformly present with a sharp

demarcated U-shaped appearance and are characterized

by a superficial diameter usually ranging from 2 to 4 mm

and a vertical extension that reaches a depth corresponding

to the superficial or deep dermis (Figure 1.2a–1.2b).

c) Rolling scars (n = 5) uniformly appear as large (up to 5

mm) poorly demarcated depressions of the skin; these

scars are very superficial, sometimes hardly visible, with

a vertical extension that is limited to a depth corresponding

to the epidermal thickness (Figure 1.3a–1.3b).

•• Hypertrophic and keloidal scars (n = 5) uniformly

appear as dome-shaped, localized increase of skin thickness

(Figure 4a–4b; 5a–5b); the dermis usually is less

echogenic than normal skin; in most cases, with the 22

MHz probe, keloidal scars may not be entirely visualized

because of their large size.